‘I didn’t want to sublimate my ego, my vanity’, she said. ‘You know that kind of ensemble feeling –"We’re all in this together." No, actually, we’re not all in this together. I am the queen. I am the star, and, you know, suck it up.’ Just as soon as the words were out of her mouth, she was modifying them. ‘Except, I don’t behave like that at work,’ she said. ‘I’m no Ethel Merman.’ *

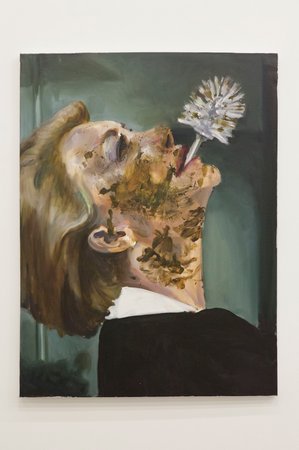

For her first major solo project made specifically for a UK regional visual arts institution and her largest exhibition of new work to date, Dawn Mellor has made a series of paintings based on the complex identity of the Southend-raised actress Dame Helen Mirren. If Mirren often plays on her Russian heritage in interviews, and draws on her British working class background in other contexts – in what has become a polarised form of role play to manipulate the media’s perception of her – then the images used in this exhibition represent her corresponding parts for film and television that show issues of domination, subjugation and control, such as in The Queen, Caligula and Prime Suspect. Mellor has translated these portraits through the dramatic lens of the two servants Claire and Solange in Jean Genet’s 1947 play Les Bonnes or The Maids. If both characters self-consciously construct elaborate rituals by taking turns to portray master and servant while their mistress Madame is away, then Mirren, who similarly flits between two different social classes to self-consciously construct her own personal identity, is seen taking turns in Mellor’s paintings to act each side of the power divide. Thus, the characters of Claire and Solange become a performative vehicle to depict Mirren – who was honoured with the 2,488th star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in Los Angeles on 3 January 2013 – devouring herself in a contemporary dramatic tension involving status, power and the polarity between self-destruction and self-emancipation.

‘I’m in a slightly weird place just now,’ Mirren said. ‘Of not being sure I ever want to work again. I want to refine the desire to pretend to be somebody.’

If the Mironoffs had been dispossessed of their wealth and their social status, the newly minted Mirrens were, nonetheless, able to generate a sense of their own exclusivity. There was ‘a slightly us-and-them feeling,’ Mirren said. ‘We were quite isolated as a family. We didn’t really have friends. Neighbours weren’t invited in. We were a little unit unto ourselves. We were trendier than anyone else. We ate yogurt long before anyone else. We were like the first people in our town to wear coloured stockings. We were kind of bohemian.’ Before the Second World War, Basil had had Communist sympathies; afterward, according to Mirren, he remained ‘extreme left wing.’ Hatred of the British class system was one of the bonds between him and his wife. His critique was ideological; hers was personal.*

In reference to this, the outside wall of the gallery has been installed with a series of small black and white paintings of Mirren as a schoolgirl, images taken from the Dame’s autobiography In the Frame. These works depict a time when the actress was becoming familiar with a 1960s counter-culture, befriending both young students from Southend art school and local musicians and of course, immersing herself in acting. Each painted image has undergone a process of détournement in marker pen and Tippex, in a manner that references traditional insurgence in painting, the failure of the early Situationist International and adolescent schoolgirl rebellion. One picture shows Mirren and her friends dressed in their school uniforms, sat in a landscape, while a pile of skulls slowly accumulate on the horizon.

Within the family, she was known as Popper or Pop, ‘because she would pop off into dreams,’ her sister said. She slept with an image of Goya’s face under her pillow. ‘I thought that somehow I’d been caught in the wrong time zone, and really I was supposed to be Goya’s mistress or wife.’ *

In her autobiography, Mirren states that she believes two performances she saw as a child in Southend – one aged six at a summer show at the end of the pier called Out of the Blue, and an amateur production of Hamlet she witnessed aged thirteen by the Southend Shakespearean Society at the Palace Theatre – were the theatrical recitals that led her to become an actress. Subsequently, she performed in school productions at St Bernard’s High School for Girls in Southend before leaving Essex to pursue a professional acting career. These moments, along with Mirren’s major roles post-Essex have effectively been re-performed and re-contextualised in Southend. Through this, the gallery becomes a stage to celebrate the transformative ritual of the aforementioned protagonist maids and a fan’s invented metamorphosis through the merging of identities, illusion and artifice. This is a process that begins within imitative and reactive role-playing, is encouraged by the traps of bourgeois society, and finally emerges into an inventive critical or politically-engaged position.

Seen within the context of Mellor’s burgeoning oeuvre, ‘What Happened to Helen?’ is a major development for the artist. Since the late 1990s her practice has taken the form of painted portraits that depict celebrities, musicians, artists, politicians, intellectuals, actresses and stars from various cultural fields. The starting point for these likenesses has always been contemporary and historical invented personas. Made in series, they assume the perspective of an obsessive fan or stalker, with the characteristics associated with pathological criminality, bad behaviour or delusional desires.

In the 2010 exhibition ‘The Conspirators’ at Galerie Gabriel Rolt, Amsterdam, Mellor exposed the competitive neo-liberalism of the art world through black humour, with its hierarchal star-system of super curators, gallerists, artists and collectors, an arena that echoes mainstream celebrity culture along with the humiliating and soul destroying effects on all those that participate actively or reactively within it. The exhibition in Southend has formed alongside Mellor’s growing sense of critical independence and allowed a series of paintings to develop with rich narratives; an act that has encouraged discourse with a new found public. Moreover, this work brings a contemporary form of critique to painting and performance, as well as extending a meditation on the possibilities and limitations of active audience engagement with object-based art forms.

Describing Composition VII by Wassily Kandinsky, her favourite painter, she said, ‘Colour, form, the appearance of improvisation: in fact, it’s intensely, beautifully worked out.’ She could easily have been talking about her own acting. Of all her theatrical influences, Mirren claims the painter Francis Bacon as her ‘great guru.’ Citing the book Interviews with Francis Bacon, she said, ‘You have to learn technique. He describes how painful the process is. How you feel paralyzed, restricted, frustrated by it. You feel like you lost your early instinctive inspiration. You have to learn it to forget it.’ She went on, ‘Sometimes you just can’t get there. Other times, you’re there without thinking.’*

In more detail, the roles within the exhibition at Focal Point Gallery can be described accurately as this: Solange, a maid, is ‘played’ by Mirren in her role as Detective Chief Inspector (DCI) Jane Tennison from Prime Suspect (an androgynous, slightly butch, older sister); Claire, a maid and Solange’s younger sister, is ‘played’ by Mirren acting in her various film and theatre roles (gangster’s moll, nude artist’s model, historical queens, maids, hysterical Shakespearean characters, etc.); while Madame, their mistress, is ‘played’ by Mirren as ‘herself’ (from her non-acting roles, as imagined by the performative fan who paints the work). The delusional fan, a painter, is played as always by Mellor herself, who never appears in the work.

‘Even as a teenager, she had a thing about regality,’ the actor Kenneth Cranham, whom Mirren calls her ‘first proper boyfriend,’ said. ‘She’s always had that hauteur. It was that thing of being apart and having poise and taking it all in.’ ‘I don’t mind if I don’t have any lines as long as I get to wear a crown,’ Mirren once quipped.*

* All quotes from John Lahr, ‘Command Performance: The Reign of Helen Mirren’, The New Yorker, October 2, 2006